October 17, 2023

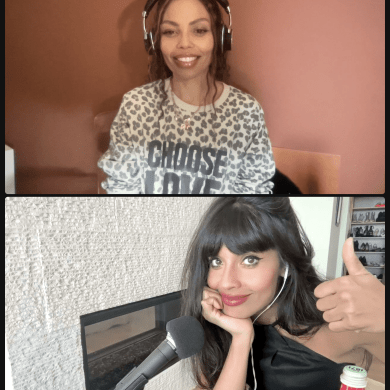

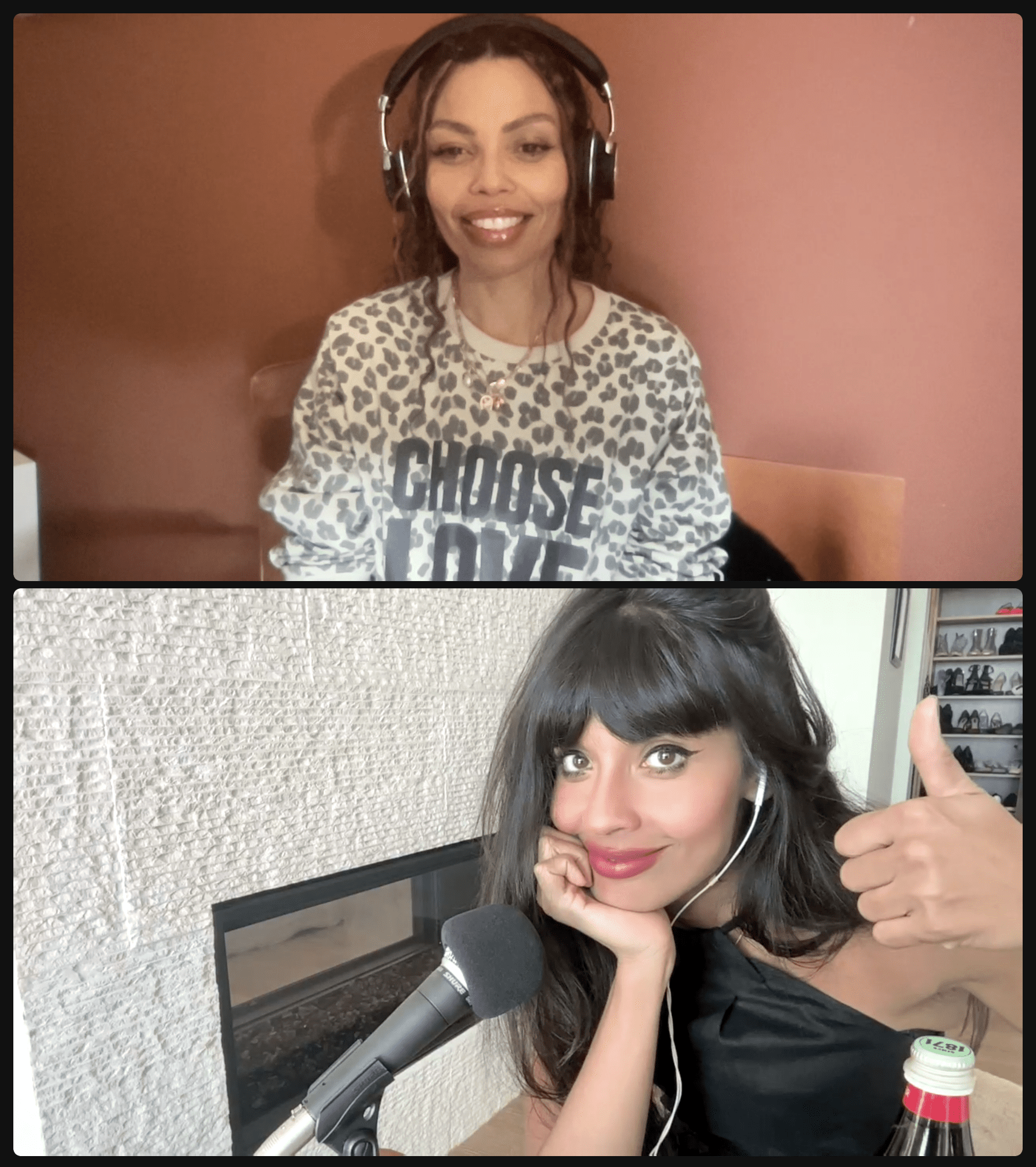

EP. 184 — How to Divorce Yourself from Modern Beauty Standards with Emma Dabiri

Jameela is joined this week by Irish-Nigerian bestselling author Emma Dabiri to find out where & why beauty standards started, how European philosophers created & influenced binary theory and what we can do to disconnect from these beauty standards. They discuss finding the pleasure in ritual and community, loving make-up (or not a la Pamela Anderson!), the importance and privilege of growing older and finding more ways to have value as modern women outside of appearance.

Emma’s book “Disobedient Bodies: Reclaim Your Unruly Beauty” is out now, and you can follow her on Twitter @emmadabiri and IG @emmadabiri

You can find transcripts from the show on the Earwolf website

I Weigh has amazing merch – check it out at podswag.com

Jameela is on Instagram @jameelajamil and TikTok @jameelajamil

And make sure to check out I Weigh’s Instagram, Youtube and TikTok for more!

Transcript

Jameela Intro [00:00:00] Hello and welcome to another episode of I Weigh was Jameela Jamil, a podcast against shame. I hope you’re well and I hope you are ready for a real schooling about beauty because my guest is a true expert on it. She’s done her doctorate on it, for goodness sake, and she has a new book out called “Disobedient Bodies” that really investigates the history of where all of our ideas about what is beautiful and not, what is good and not, what people are supposed to look like, where all of these things come from. And I think, you know, we have a kind of rough idea about that on the Internet, that some of it’s linked to patriarchy or some of it’s linked to, you know, white supremacy and colonization. But in this episode, my guest really gets into the nitty gritty of exactly where it came from, when it started to happen around the world, what the world looked like before all of this shit that now has ruined most of our self-confidence and how we can start to understand these systems in order to be able to break them as individuals. My guest is Emma Dabiri. She’s an Irish Nigerian bestselling author, academic and broadcaster. She’s super smart, super kind and so well educated and research that I had to fucking drink like three coffees before this episode just to just to make sure that I was on my my game because she’s just super clever. She’s also outrageously, outrageously hot, according to modern day beauty standards. She’s stunning. Fucking stunning. So it’s very easy for you if you end up seeing a picture of her or you’ve seen any videos of her before, you listen to this chat to be like, “I don’t want to fucking listen to someone who looks like a perfect goddess tell me about beauty standards”. I talk about that with her. We kind of challenged that at the beginning of this episode to kind of get that shit out the way and and address that elephant in the room. But I, I do think that she has done so much extraordinary work to really unpack this and that it is important to not dismiss people cause of their face in any way. And it’s just an excellent understanding of how we got to this mess in which the statistics on self-esteem are the worst they’ve ever been in teenagers and in adults like how did we get here and how can the decisions that we make around the way that we look actually be choice? If we’re constantly being poisoned and bombarded by our outside culture and society? So let me know what you think. I think you’re going to find this incredibly interesting. I think it’s really going to hit home with you. I think it’s going to really bring up some uncomfortable questions for you, and go and read her book, “Disobedient Bodies,” which is out now. This is Emma Dabiri.

Jameela [00:02:31] Emma Dabiri, welcome to I Weigh. How are you?

Emma [00:02:52] I’m very well, thank you. How are you?

Jameela [00:02:54] I’m so good. I’m so happy to have you here. I’ve been a long term fan of yours, and I am really, really excited to get into the subject of beauty with you today. Before we do, how has your mental health been of late? It’s been a weird year.

Emma [00:03:10] Oh my God, it’s been a weird year. It’s been a weird few years, hasn’t it? You know what? It’s been like a lot better than it’s been at many previous times in my life. I’ve never actually really had therapy. I know that that’s something that I very much need to do and that I’m prioritizing. And actually, interestingly, I’m starting therapy tomorrow. Yeah, I feel like I’m in a place where my mental health is actually like, better than it’s been at many previous points in my life. And yet it could be better. I think I’m really like, I’m really ready to just be operating at like kind of optimum levels.

Jameela [00:03:52] You have a book out at the moment. It’s just come out. It’s called “Disobedient Bodies”, and it is about the kind of history of where beauty decided upon and the impact it has on us and all these kind of different intersectional issues that help define different beauties in different parts of the world. And before we get into what this book is about, I wonder if you’ve experienced pushback because you are so very obviously very beautiful and perfect in every way according to current mainstream beauty standards. Do you, have you experienced any kind of eye rolls of like “the fuck is she going to tell us about beauty, about trying to ignore beauty standards, etc.?”

Emma [00:04:37] Not, not to my face.

Jameela [00:04:40] Right.

Emma [00:04:40] Not that I’m aware of.

Jameela [00:04:40] Oh I’m glad to be the first. And also, I don’t mean that in a in a thorny way. I mean that in a very just curious way.

Emma [00:04:47] I’m not saying that that hasn’t happened, but I have not, not that I’m privy to, you know?

Jameela [00:04:54] Right, right, right.

Emma [00:04:55] It’s also, I though, I think there’s a very interesting dynamic when you’re a person who at a later point in your life is perceived as possessing this thing called beauty that we are conditioned to aspire to, but when your formative years were such that you were very, very far outside of the beauty standard. So you’ve got this kind of exterior of what is perceived to be beautiful, but like inside you’re that person that was formed, your personhood was formed as somebody that was like excluded from beauty. So I think there’s like an interesting, like tension there. Do you know what I mean? And I also feel like being in inside and outside of something can give you an insight into the frailty of it and the fact that possession or not of beauty as a marker of your worth, your value as a human being of your humanity is a very, a very treacherous sands, you know, on which to kind of try and to try and build any, any foundation. You know, it’s a very it’s a very fragile space, I feel, on something that is so arbitrary, contingent, ephemeral.

Jameela [00:06:18] What does ephemeral mean?

Emma [00:06:21] Oh, ephemeral is something that is transitory, something that has like a short life. It’s actually like a concept that I talk about in the book because it’s a um, it’s something that you see in Japanese esthetics quite a lot. This valuing of the short lived nature of something that’s beautiful. So I think in our culture we try and like preserve youth, for instance, we try and preserve certain things that are perceived as beautiful. And in Japanese culture, there’s this recognition that actually the ephemeral nature of something is part of it’s, it’s part of its beauty. It’s why, for instance, like the cherry blossom celebration is such a significant part of Japanese culture because it’s beautiful, but it is also like very temporary.

Jameela [00:07:12] That’s fascinating, and the reason I ask that, like I said, was not to in any way try to discredit you, because I definitely relate to someone who, you know, at the beginning of my career was called a monkey for the way that I look. And it’s the same exact face that I was ostracized when I was younger for that now, because of the transience of beauty standards and the speed at which they evolve, or maybe not evolve, but change, all of a sudden features of mine that I was made fun of, like I remember being told by a photographer that my lips look like two slugs fucking and people would make fun of me for having big lips. And then now all of a sudden,

Emma [00:07:47] Yeah

Jameela [00:07:48] People pay a lot of money for big lips, and that’s considered acceptable. Or my skin color, all kinds of different things about me were considered bad, including curves going out and then in, and now they’re out again, like is it’s very, very tricky to try to come to an acceptance of the fact that you now suddenly for the same exact thing exist within privilege. It doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t accept and, you know, acknowledge it, but I think that it is an interesting base to exist in and to write from. And also one of the more, one of the more distressing things about this subject is that if a woman and this is something that massively needs to change and I think your book is encouraging this change is that if a woman in particular or anyone actually of any gender were to make some of the points or highlight some of the histories and the simple fact that you put in this book so beautifully, if they did not exist within what is currently deemed as whatever bullshit beauty standard we’ve been fed, then they are more likely to be dismissed and called bitter or jealous. And so there’s this really gross line that we have to walk. And also coming to terms with the fact that someone within privilege is the same way that will listen to a celebrity talk about socioeconomic disparity when they’re living in their mansion or will listen to a slim person like me when I call out Fatphobia in a way that we won’t listen to a fat person. It is this really frustrating thing, and I’m glad that you have not been discouraged away from having this conversation because it needs to be had. And I think you have so much important insight in this book that I’m excited to get into today. I just had to address the stunning elephant in the room. That was all.

Emma [00:09:32] Thank you. I still feel like, Oh my God, like, are you describing me, are you describing me? Are you still, are you talking to me? I feel like I was in an interview recently and somebody asked me when I came to, to recognize that, that I was beautiful. When did I know that I was beautiful? And I was just like, what? Like, I just can’t like, I can’t, I can’t answer that. And I couldn’t do it. I think it’s also like part of my, like cultural background in that like I come from like far more so than Britain, even like a culture of you know, like extreme self-deprecation to the point where, like the something I talk about in the book.

Jameela [00:10:11] You’ll be eaten alive in Ireland for that!

Emma [00:10:13] Yeah, yeah, yeah. Oh god Ireland, yeah. So this idea of, of notions and it’s an abbreviation of notions of grandeur, but if you did anything that was, so I used to, I used to have like really good posture that my mom had like drilled into me, the people would be like, oh my God, look at her. Like walking around the place. Who does she think she is? You know? So I started notions, that young ones got notions. So I started like slumping because I was just like, Oh, I can’t look like I can’t look like I’m proud. Jesus Christ.

Jameela [00:10:52] Also, I think it’s important to highlight which, you know, you discuss your history in which you spent the first few years of your life, formative years of your life in Atlanta, which has a large population of color, specifically black people, and then moved over to Ireland, where you then become, go from being in the vast majority to the vast, vast minority, in which then people started to make fun of you and the way that you look. And I think that’s kind of the beginning, from what I understand of your journey, that you are different and the beginning of you understanding that you’re being objectified for better or worse. How has that shaped your desire to write this book and to whistle blow this sort of subject?

Emma [00:11:36] Yeah, the different spaces I’ve been in and the different experiences I’ve had of being, like considered beautiful or not, like really gave me a strong sense of being like, this cannot be the thing, like it makes me feel really, really insecure and like kind of nervous and scared that that’s the thing that, like my value as a human being is judged on because it’s like, well, what if you’re not perceived as beautiful? That cannot be the thing that we determine somebody’s like, a woman, specifically, a woman’s value and worth upporn. I write in the book about, you know, very much being an outsider growing up and there being like a big distance between certain things that I was told were true and the reality of things. I saw that like there was a lot of hypocrisy in the world, you know, that there were, there were people that would like hate me, hate me on site because of racism. I learned that from like a young age. And also this is Ireland. Like this is in the 1980s. Ireland is a far more diverse country now than I could have imagined when I was a child, but it was like a 99.9% white country. Like I was very much an anomaly. Many people had never seen a black person before or any person of color. I know because they would tell me. They would announce that to me, and they’d come over to, you know, look at me and like touch my hair and stuff. But then there was also and I mention this in the book, like Ireland is itself a colonized country. It’s like England’s like first colony, really. It was colonized, you know, for 800 years. And that has a profound impact. But I feel the combination of like those two things put me in a position where I didn’t really take stuff necessarily, like at face value. I didn’t believe what I was told in terms of what I was learning in school necessarily. I knew that there were other histories. There were there were alternative ways of looking, of looking at things. So I always I read like a lot from a very young age, and I was always kind of like looking for my own answers.

Jameela [00:13:43] Mmhmm. You spoke to just now an insecurity almost that comes from having value placed on something that can be as transient as our appearance because either our appearance can change or especially if you’re a woman, the standard of what is a good appearance can change very swiftly.

Emma [00:14:00] Mmhmm, mmhmm.

Jameela [00:14:00] We just saw it in the last two years where curvaceousness was suddenly incredibly popular and people were pumping their bodies up to be more curvaceous in certain areas. And then all of a sudden, at the same time as like injectable weight loss drugs came into power, that has gone away again and everyone’s having like ribs removed and taking immense risks with their lives and health in order to achieve a sort of late nineties, early noughties, heroin chic thinness like that’s come back in your noticing, like the way everyone standing everyone’s doing the like pose forward with their shoulders, like kind of creating that big clavicle shelf that you can put your keys in, your keys and your condoms in. And it’s really, it’s been really wild to watch how fast the body positivity movement suddenly just, everyone just stopped talking about it. And it’s a weight loss culture again. And so beauty of the face and skin color and ethnicity and the kind of cherry picking of white culture of ethnic features. So whether that be the slanted eye or the pumped lip and because technology in, I guess the aesthetics world and cosmetics world has shifted so much that now you can just put a thread inside someone’s cheek and boom, suddenly they have an eye that looks more East Asian, you know, or they can emulate the features of all kinds of different cultures and they can put spray tan on and they can look brown, etc. So because we have commodified and I guess democratized racial ethnicity and the features of, of racial ethnicity, it means that there’s just this kind of big blur that is ever changing and ever shifting. And that feels very deliberate. It feels very deliberate to put specifically women to target specifically women with the anxiety, a feeling as though of being given something to hold, which is “you have been declared beautiful and now you have to hold onto it for as long as you can.

Emma [00:15:50] Mmhmm.

Jameela [00:15:51] It’s like you being handed grenade of saying you have just been deemed worthwhile. Better keep up. Better keep that up.

Emma [00:15:57] Yeah.

Jameela [00:15:57] Don’t age. Don’t lose weight. Don’t gain weight. Unless we tell you to. It’s so weird to have that imposed upon you as a human being who just wants to learn and live and laugh and cuddle and come and eat and all the different things that we want to do. It’s such a weird burden to be told either you are or aren’t in the club. Therefore, you must try to achieve status in the club or maintain status. It’s so scary and unhealthy and such a like diminishing and reductive ambition to give us, and in the book you talk about the point at which that entered our culture because it wasn’t always that way. Women were not always perceived as just having value in our appearance.

Emma [00:16:32] Mmhmm.

Jameela [00:16:32] Our work was not diminished. Our value in society was not diminished. Can you talk about when that happened? Where mind

Emma [00:16:40] Yeah.

Jameela [00:16:40] And body became separated.

Emma [00:16:41] Yeah, absolutely. I say that like a culture that places such overemphasis on the way that women look is one that sees women as subservient to men. So even if you are ranking highly within that hierarchy, it’s because you’re positioned in a system where you are still seen as subservient to men. So I don’t want to, like, invest all my effort into like fighting to be objectified. I want to like, transform the world in which, like the objectification of women is so preeminent. So I really wanted to understand why there is so much emphasis placed on the way that women look in comparison to men like I wanted to more deeply understand that myself. I also knew that the type of patriarchy that we live under is not, we’re often told it’s from time immemorial, and it’s kind of like it’s, it’s universally been.

Jameela [00:17:45] We’re told it’s biology, right? We’re told that that is just nature. It’s not nurture that men are designed to be, that men are wired. They love to say wired, not as in men, as in like whatever, our culture loves to say wired.

Emma [00:17:59] Haha!

[00:18:00] And, and, and by the way, I don’t think there is no truth in this. Right. That men could be more physically motivated and I guess visually aroused, etc. And so they are looking for a you know, they are looking out for beauty more. And then women tend to, not always, but tend to look more for kind of humor, security, etc., all these kind of different things that we respond to. But then they also use that to justify men’s interest in women being that of much younger and younger and younger girls to the point where they’re barely pubescent. And it’s like, well, you know, we’re just wired to look for someone who’s more fertile.

Emma [00:18:36] No. Haha!

[00:18:37] And it’s so weird that you go to other countries in the world and you don’t see a similar disdain for an older face. You see young men like in Italy, calling out to older women and like losing that shit. And I think the same thing in certain parts of Europe, certain parts of India. It’s not to say that young women are not considered, you know, desirable all around the world and that there’s no truth to the fertility thing. But how much it’s being pushed to justify a kind of porn centric environment feels incredibly disingenuous, given that in parts of Africa and parts of Asia, this does not exist at the same level that it does in the West.

Emma [00:19:14] For sure. I don’t think it’s to do with biology. I think it’s to do with the particular brand of patriarchy and to do with power and power dynamics. And I taught African studies for like a long time. So I knew about the way that women’s position in society across the African continent had directly deteriorated under colonialism. So colonialism didn’t liberate African women. Colonialism didn’t bring progressive gender norms to anywhere that, that it colonized in the way that, like it’s kind of presented as, as having done. But often the, the roles that women had, the positions that women had actually like severely deteriorated. I talk about that in the book. I already knew about that. But I also was just like, oh, what was it, was it always this in Europe? What was it like in different historical periods? I started to read about the enclosure of land acts, something that I’m long fascinated by because actually I said Ireland was the first English colony and it was, however, those processes of appropriation of the land that the English did as they expanded out into the world, they had actually kind of finessed at home by the landed gentry, the aristocracy actually, like enclosing the common land. I’m going to, I’m going to get to the point back to beauty, but enclosing like, enclosing the common land and making it private property and driving off the, they weren’t poor yet, but driving the people who had you know gotten sustenance from the land, off of the land which became enclosed in private property. When everyone had had access to that land, women had access to the land in the same way that men did with the transition to capitalism, which was happening with the enclosures. This is also the period of the witch hunts. Now, the witch hunts were a direct attack on the power of women in those communities who were having their land stolen from them by the landed gentry and the aristocracy. And it was really fascinating to see that, like many of the women that were, like branded as witches were, in fact, doctors, often midwives. They were women that, you know, were often very knowledgeable and powerful in their communities and had, like, these spheres of knowledge and power. Those spheres where women had like, you know, autonomy and power. Were intentionally targeted in this transition to capitalism. You also see like the beginning of the, this division, this distinction between like the domestic and the public space. And in this transition to cap- to capitalism, you see men start to become, they have access to working and earning, becoming wage earners. Women do not have access in the same way, even actually, if they can work and they become wage earners, the money is like belongs to their husbands. So you see this thing where women become increasingly dependent on their husbands, where they had access to resources, where they had access to spheres of influence and power. All of these things are targeted. Their opportunities are in many ways diminished. And with the reliance on wage labor that everybody is coming to have, men have access to that in a way that women don’t, so women become increasingly reliant on their husbands. And we see this gradual process where women’s role is increasingly like circumscribed and reduced, which ultimately, like is part of what contributes to women’s diminished role as these wives, these dependents who are just these kind of like decorative accessories. And you see similar processes happening in the parts of the world that England centuries later, after that, in the parts of the world that England and Britain colonized.

Jameela [00:22:56] And which century would you say that had occurred in?

Emma [00:22:58] So with colonialism, the example I give for, I focus for that in Nigeria and I’m looking at Nigeria is colonized in the late, the late 1800s, early 1900s. So it’s relatively recently.

Jameela [00:23:12] It’s so frustrating how recent this is and how speedily effective it was. Can you talk more about the separation of mind and body and how mind was attributed more to being something that is male and body being attributed to something that’s more female?

Emma [00:23:29] Yeah, absolutely. I love, I love this. I’m kind of obsessed with-

Jameela [00:23:32] Mmhmm

Emma [00:23:33] Cartesian binaries. One of the questions that I had in writing the book was, where does this deep sense of like self-loathing about the body that I’ve, about my own body and appearance that I’ve experienced and that most women I know have experienced are, or are experiencing? I’m like, like, where, where does it come from? Why is it so recognizable to so many of us? And we’re told that it’s the result of unrealistic beauty standards and advertising. And it’s not to say that that stuff is not without huge influence, but why does it find such fertile ground? You know, why is it so, why does it impact and affect us so deeply? And I was just like, there’s something far more deeply seated. So I yeah, I take it back to, like, to Plato. And this can be traced at least to Plato, if not earlier. But with Plato, you have this this idea kind of central to his philosophy of this separation between the body and the mind, okay. And that’s a distinction that is kind of a cornerstone of like, of, of Western discourse. There’s lots of other cultures that don’t have that same distinction that emerge out of different, you know, kind of philosophical and metaphysical traditions. But that’s a central tenant of Western philosophy. But if you fast forward like many centuries to just before, like the European Enlightenment, and you have René Descartes, like a hugely, hugely influential French philosopher, even if we don’t we’ve never heard his name, we’ve never heard about Cartesian binaries, the way in which we’ve organized the world and that we understand ourselves and each other is a direct legacy of his philosophy. So this binary view of the world are categories that exist, you know, like man, woman, black, white, gay, straight, good, bad, perfect, flawed. All of these binaries come from, we’ve inherited from this dualism, this Cartesian dualism. And within that binary, like one of the categories is always inferior to the other. And there’s this, there’s this hierarchy that exists between them. So from Plato and then further enshrined in Descartes, you have this notion that within that mind body separation. Men, European men, come to be, the mind is seen as superior to the body. The body is something that is like subservience to the mind, you know, it needs to be like controlled and disciplined. And it’s like one of the quotes I used in the book from Saint, Saint Augustine is like the slimy desires of the flesh. You know, the body is this kind of like gross.

Jameela [00:26:12] Unintelligent meat puppet.

Emma [00:26:15] Haha! Very good, that’s it.

Jameela [00:26:17] Which is

Emma [00:26:17] Perfect

Jameela [00:26:17] It feels penile now that I say that, but.

Emma [00:26:21] No, no, no I actually, no but that’s that, that’s the kind of energy. So the mind is the place of the, you know, cerebral, intellectualism, lofty pursuits. The mind is associated with rationality and comes to be associated with European men. Women and racialized others come to be banished to the fleshy confines of the body. So in Western discourse, there’s like this deep seated kind of contempt for the body. And then there’s also this positioning of women and racialized others as bodies, and European men as these kind of unembodied, rational, objective, objectivity. We’re subjective, they’re like objective, you know, kind of outside of the body. And, and all of that kind of scorn and disgust that exists towards bodies, inferiority that exists towards bodies is transferred then to women and to, to racialized others. And this is like a deep seated thing in Western discourse. So I was fascinated to know what about cultures that emerged from a different, have a different relationship to the body come out of a different metaphysical kind of tradition? What’s their relationship to the body and is it gendered in the same way, you know?

Jameela [00:27:32] Mmhmm. And what did you find?

Emma [00:27:33] I found out, I found out quite a lot. So again, like one of my main reference points is, I’m Yoruba, it’s my paternal ancestry, but it’s also like the culture that I taught about for a long time. But I really wanted to expand. My first book, Don’t Touch My Hair, was, you know, everything was, it was all kind of African and African diaspora history. And with this, in cultures where there isn’t this separation of the body and the mind, and there isn’t this idea that they’re immutably separate and that one is like superior to the other. There’s not the same hatred of bodies and there’s not this, I think somewhere you really, a way that you really see it play out is and this was something I experienced like very dramatically in my own life coming from Ireland as a teenager in the nineties and there being this like huge pressure to be incredibly thin, like the body standards, beauty standards, was like very, very, very skinny. And often when I’m speaking to English people, they’re like, Oh yeah, was that heroin chic? And I think that like was part of it that turbocharged it. But I think it’s something that actually far predates that. And then so but comparing that to being like in black culture as to being, you know, in Nigerian culture or to being in black America where like a far more fuller figure was, you know, like appreciated. And when I was researching, in the book, I talk about like the Yoruba goddess Oshun, who is the goddess of like beauty and like love and fertility like and she has all of these praise songs called Oriki and one of her praise songs describes her as a corpulent woman, a woman who cannot be held around the waist, a woman who cannot be embraced around the waist. And I was just so struck by how like vastly different that is to the cultural context and norms around women’s bodies that I grew up in.

Jameela [00:29:31] In the West.

Emma [00:29:32] Within this part.

Jameela [00:29:32] Yeah, I mean, I’ve, I’ve said this before about India and Pakistan that for a long time I think it’s changing now, unfortunately. But-

Emma [00:29:42] Yeah

Jameela [00:29:42] You know, you were I mean, also not on foot. I, I don’t even know what to think because I don’t think it’s right to have any kind of body norm, but it was just so interesting to see

Emma [00:29:49] Yes.

Jameela [00:29:49] That when I would go back and forth between London and Pakistan in London, I was never thin enough, and in Pakistan I was never curvaceous enough, you know, because it was a sign of you having the money to eat. I remember there were friends of mine who were from Nigeria who would tell me and I don’t know if these were like old wives tales or not, but they would tell me that there was some girls in the villages that they used to come from that would take like chicken hormones, like they would be encouraged to take chicken hormones in order to be able to fatten up because then you would look like you come from a family that has a lot of money and a lot of wealth. And so you had to eat as much as you could to try to make sure that you looked as though you were good stock, that you were healthy, that you were vibrant, that you were fertile. And so at that same time, this was the kind of like beginning of the tanning craze really starting to reach the United Kingdom. So everyone was like orange, you know

Emma [00:30:42] Haha

Jameela [00:30:42] Because it hadn’t really evolved yet and so everyone was orange trying to have a skin color like mine. But then whilst at the same time there was racism around a certain skin color, but they want it to be browner than they were, maybe not as brown as me. But then I would fly and go over to Pakistan, where everyone was taking bleaching cream to try to become

Emma [00:30:59] Yeah

Jameela [00:31:00] Fairer skinned and white is right, and the adverts are still fucking outrageous in Asia, both in East and South Asia, how desirable you are, whether or not you are light skinned. But everyone trying to almost kind of like, like burn the brown off them, not, you know, I wasn’t allowed to go out into the sun when I was in Pakistan because they did want me to be too dark skinned cause that meant unattractive. So I was just like, all these constantly shifting narratives that exist on the same planet at the same time on the

Emma [00:31:30] I know.

Jameela [00:31:31] Same day are so conflicting, and it was so confusing to me. I had no idea what to do with it, but I just chose whatever was the norm of the place that I was going to spend the most time. So it was England and I was like, I have to fit in. I have to not be left behind. You know, I don’t want to be excluded from the tribe. And so that’s where my kind of anorexia came from.

Emma [00:31:52] Yeah.

Jameela [00:31:52] Was just trying to conform, trying to fit into this uniform that was prescribed to me, that I just took as, my mother subscribes to the same uniform, like form of beauty set as my grandmother. So I just presumed this is what it’s always been like. And there is a feeling of us being dismissed when we complain about this of like, this is how it’s always been. And it’s so important with your work that you highlight that these are very modern shifts and hypocrisies that exist to this very day.

Emma [00:32:20] And I really feel like you said something that when you said lots of things that are really okay. First of all, I think like having that insight of being in two, of two very different places and, you know, having that experience that you’ve had is so valuable. Like I think people that have experienced those contrasting, conflicting ideals within hours of each other, you know, because literally it’s the space of like taking a, taking a flight, have a lot of insight and a lot to contribute to these, to these discussions. It should be kind of like a body neutrality. Like one of the arguments I’m making is it’s not about replacing one beauty standard with another, but I was actually very fascinated by this even idea of the standardization of beauty. Because now we have a situation where by you’ll have different standards in different places, but the notion of standardization is kind of consistent, that there’s some sort of standardization is consistent across the world. And I was really interested again, like with kind of pre-colonial Yoruba, and I was looking at the Proverbs. So there’s this argument that like the, the reason that beauty is perceived as this, and this is across the world now because, you know, Western norms have been spread

Jameela [00:33:30] Mhm.

Emma [00:33:32] Forcibly. This idea that beauty being primarily visual, primarily something that we know through sight is the result of something called ocular centrism, which is like, which is European, and it’s in European culture, that sight is seen as the noblest of the senses. And there’s a Yoruba sociologist who wrote a book called “The Invention of Women”, and in that she’s saying, like in kind of traditional Yoruba culture, there were other senses privileged, like, you know, as much as sight. So beauty in that context wasn’t necessarily something that could be, you didn’t look at something and think, I know what that thing is based on how it, on how it looks. It was other things that determined knowledge of it. And then I was also really fascinated by looking at Yoruba proverbs and this notion that. I got, I got the feeling that there wasn’t like, it wasn’t like, distinctly: everybody has these, these features and these are the features that, that equal, that equal beauty. But it was more like contingent and case by case specific. So there’s, there’s a proverb that’s like one his beauty is enhanced by their smallpox scars. So I was just like, Oh, that’s really interesting because that’s not like a, that wouldn’t be kind of considered like a norm in our culture. There was also this idea that, there was also a proverb. Obviously, like I’m mixed, I have a white parent, and so that’s why my complexion is what it is. But in Yoruba, in Yoruba even outside of any mixing, there are different, there are different complexions, you know. And there was a proverb that was like one who, whose complexion is as beautiful and as dark as the seed of the Ackee apple. So a very, very dark complexion. And then there was another proverb that was like one whose like another praising proverb, but it was for somebody whose skin is red, like palm oil. And again, it was, it was this idea that you, you weren’t perceived as being beautiful or not beautiful based on your complexion. You could have any complexion and be beautiful. It wasn’t like there was this standardization that means this, you have light skin so you’re automatically beautiful. It was more like, yeah, it seemed like it wasn’t as standardized. It was like case by case specific. And I think it’s this idea of standardization that there’s this set of perceived features that gives or excludes from beauty that is, that is so tyrannical, you know.

Jameela [00:36:06] And is what you’re describing in Yoruba the pre-colonialism or pre-patriarchy or post?

Emma [00:36:14] This is, this is not now, this is not now like this is this is pre-colonial.

Jameela [00:36:20] Right, right, right, so isn’t that interesting. And so do you believe that it is a deliberate attack on our gender, which I think you’ve kind of, you know, hinted to already, but do you believe that this is an attempt to diminish our value and to distract us and to keep us anxious and, you know, not necessarily afraid, although some of us are, but it’s a way to take our money. We are 80% of consumers. It is a way to distract us and keep our eye off the ball from, from not just like growing our whatever, our business or our career, but growing ourselves, growing our confidence, growing our mental health, growing our life experience.

Emma [00:37:04] Yeah, I will come to that. I’ll come to that in one second. I just want to, like follow up on what you asked me just previously to that about, just to talk about like that Yoruba standard being pre-colonial like there is obviously like, you know, colorism in Nigeria now, but Nigeria is one of, or Africa. I’m not, let me say Nigeria. I mean, it’s invented by the British. But Colourism in that context is, you know, the direct result of colonialism and like Western and Western beauty standards, it’s not something, as far as I’m aware, that predates that. You know, in some other contexts, in other parts of the world, there was already, obviously it wouldn’t have been called colorism, but there was already that kind of hierarchy that then kind of became turbocharged by global beauty standards and colonialism. But in that context, it’s something that is like, you know, introduced from outside. So I’m talking about kind of before the introduction of that tyrannical and oppressive norm or not norm, but beauty standard, rather. What you were asking me. Yes. So let’s talk about capitalism. So under capitalism, there is this drive for constant, constant productivity, constant improvement. You know, we, we always need to work harder, be more productive, do better. Now, when we’ve already been like for millennia, conditioned to believe, you know, that our, that our bodies are like kind of all important and also like are not good enough, any narrative that tells us that our bodies and our appearance need to be, you know, constantly policed and improved, it finds quite fertile ground. You know, we’ve become quite malleable. We’ve become those narratives of capitalism can inscribe themselves very well upon our flesh. And this striving for constant perfection, again, is not something that you necessarily, so perfection is like this ideal that we aspire to, that we assume is probably universal and foundational. But again, when I when I was looking at the Navajo, and when I was looking at the Yoruba, again pre-colonial, it was this notion that perfection wasn’t actually the ideal to aspire to. Perfection is seen as an extreme. And harmony and balance were the, were the, were the goals to aspire to. So I was just like, oh, like what would a beauty culture that isn’t striving for perfection or is informed by cultural norms that don’t strive for perfection but strive for harmony and balance, what would that look like? And interestingly as well, in Yoruba folklore there, there are a lot of examples of a suspicion that very beautiful people are held in. And not just women, but men as well. And in the folklore, you see these very beautiful people, both men and women who appear somewhere and usually cause some kind of like disaster, but they have their skeletons who have like acquired all of these beautiful body parts. Like along the way to this place where they, like, end up through nefarious means. And so they have this beautiful, like edifice, but it’s disguising something that’s really ugly. And actually, that also was making me think about this cherry picking of features that, that we see currently, you know, as it’s like all that really, like kind of has parallels, has parallels with that. So yeah I think our kind of goal, our striving towards perfection, and that being pushed as you know what we need to be doing has quite disastrous consequences on us.

Jameela [00:41:15] We already touched on this a little bit before, but bringing patriarchy into this. You talk in the book about the patriarchal gaze, about centering ourselves towards the male gaze and how this is kind of underlying pressure from when you’re young to do so in a way that doesn’t, you don’t really feel even aware of, it feels, you know, it feels like your choice in as we’ve gotten older and as, you know, feminism’s become more and more diverse, we have been told is empowering and that, that is a form of empowerment to have the right as a woman to choose to define yourself via the patriarchal gaze, that we’re just sort of like, it’s turning into like more and more of a labyrinth as to like, what is empowering? How do we know if it’s a choice? How can it be a choice if we’re being bombarded with this information? And you point out the fact that for many people, even when there are no longer men in the room, that anxiety exists and is now transferred from just being something that we worry that men will look at us for, we compare ourselves to other women. You talk about this kind of scan that women quickly do.

Emma [00:42:22] Yeah.

Jameela [00:42:22] Assume that they meet each other and that the way that we scan ourselves in the mirror. And interestingly, like I find that in my experience, in my experience only perhaps that the lesbian women that I know do not carry that same exact beauty standard in themselves. They don’t feel a need. They don’t have any desire to participate in it. And that is in and of itself challenging to, is this a choice for some of us?

Emma [00:42:53] Mm.

Jameela [00:42:53] Can you talk about how we could break away from something like that, how we can get out of this mindset? Is it realistic to be able to break out of this mindset? Because it’s so reductive and it’s so exhausting and it’s just getting worse and worse with every year? I spoke recently out on Instagram about this, how bad it is for my brain to be in Los Angeles, where women are no longer aging. I’m just not seeing women age and and I can’t tell the age of anyone, I can’t like. Everyone looks 40, whether they’re 18 or kind of, or much older than 40,

Emma [00:43:26] Haha!

Jameela [00:43:27] Because everyone’s had all the same work done. And I don’t mean in any way to mock anyone. It is genuinely disturbing me how normalized and prevalent it is for there to be such an anxiety of the signs of experience showing on your face, which is becoming worse with Instagram and filters and everything, and our obsession of like nonsensical obsession with youth. But it isn’t as bad almost anywhere as it is in the kind of big cities of certain cultures where capitalism is thriving. What the fuck do we do?

Emma [00:43:57] Mm.

Jameela [00:43:57] How do we get out of this? How do we get out of the point where, when we’re standing alone or with no men in the room, we are still catering towards the patriarchal gaze, even if we think it’s for us?

Emma [00:44:06] Yeah, cause I feel like we’ve internalized, like, the male gaze, you know? So it’s not just, it’s not just purported by men. We kind of all internalized it. Like, I really love John Berger’s, I mean, the classic text “Ways of Seeing” where he talks about the objectification of women in an oil painting. And again, this is, you know, kind of the transition to capital and like private property and like ownership. And he talks about this painting called like “The Judgment of Paris,” where the idea of like this woman being judged on her beauty and then deemed “the woman who is the most beautiful” is like given the prize and the introduction of that idea and its relationship to visual culture, objectification and capitalism, you know, it’s not necessarily just a natural thing that exists in the way that we’re told it is. I also feel like strongly that things like, so competition and jealousy and envy, jealousy and maybe let’s say are I guess they’re like human emotions that would exist under, under any political or social system. But we live under a social, political, economic system that, you know, not only valorized and encourages, but actually kind of demands like fierce competition and hyper individualism. You know, it prioritizes competition over cooperation. And so I feel like for women, like whose, whose value has been for so long reduced to the superficiality of their exterior, of their appearance. One of the arenas where this competition, you know, kind of most ferociously plays out like is within, is within beauty. And I really, oh I’ll come to aging in a second. But I really strongly feel as well that where women are, like, pitted against each other and set up to see each other as competition, we do have some autonomy and like power over our lives, something that can be a strong antidote, you know, against that is actually, you know, the cultivation of and like, I honestly don’t think this is, this is wishy washy. I think this is something we can really like, you know, kind of practice trying to, trying to embody is really through like, you know, the intentional like cultivation of like, you know, solidarity and sorority. And I feel like doing more- something I talk about in the book is like, you know, kind of intentionality and like ritual. And I even think like in beautification, like beautification processes, you know, kind of groups of- the book starts with me getting ready with a group of like female friends as a teenager, you know, for a night out and actually like the importance of those spaces, even though they were underpinned often with a lot of kind of, you know, checking each other out and competition. But I really feel like contesting and challenging this message that we’re always given that our primary importance and site of value is, is our appearance is really crucial. For me personally, you know who did but who did believe that to a large degree, like honing my sense of purpose and like, you know, honing the sense of like what I have to contribute to the world beyond like whether or not, you know, some kind of random man thinks I’m hot or not was just yeah, it was just really important.

Jameela [00:47:54] You said you were going to get back to the aging thing.

Emma [00:47:56] Aging? Yes. So again, it comes back to this binary view of the world. You know, this, this distinction that’s seen between, that’s seen between like young and old and again, within the binaries is this hierarchy. One is always superior to the other one. But when I was looking, for instance, at like pre, with Ireland you have to go even before pre-colonial. You have to kind of go to like pre-Christian, but you’ve got this thing where like the hag and the maiden are not actually seen as, they’re seen as part of the same whole and time is understood as unfolding in not this linear, this linear way where like you’re young and then you’re not young anymore and you’re old and they’re like discretely distinct from each other, and there’s this binary, but actually the, the hag and the maiden in this kind of perpetual cycle of renewal and aging, renewal and rebirth so they’re not imagined as like immutably different from each other. But again, it’s not the binary, it’s a far more holistic way of looking at, of looking at things. And I just wonder, the book is a kind of, is an argument against dividing the world like into binaries or questioning these binaries through which we, through which we view the world. And also again, like in Japanese culture, I was writing about the fact that like as I was saying at the beginning, this thing of ephemerality, but also like impermanence being seen as beauty and actually the signs of something aging, the signs of something like no longer looking, quote unquote, perfect. That being the beauty, because that actually reflects the passage of life, you know?

Jameela [00:49:53] Mhm mhm. That’s exactly how I feel, and it’s something that I feel so passionately about when it comes to aging and again, without judgment cause I can understand where all of this comes from. But again, it’s harder to take seriously as totally fully being a choice when we are told the world will leave us behind if we no longer look young and fertile and useful and sexy to specific people. I despair of this normalization that I am supposed to erase the signs of my journey. I’m supposed to erase my survival. I’m supposed to discount how amazing it is to have the privilege of getting older. I don’t want to put painful, expensive shit that I have to keep spending money on into or on my face that could go wrong and then I have to pay to fix it. And even then it might be really hard or impossible to fix it. And it’ll only give me further dysmorphia about my face. And I will, it kind of never ends when it comes to needing to fix this and fix that. I don’t want to have this kind of uniformed face that I’m seeing everywhere in all the big cities around the world. I’m really, really deeply concerned that we are erasing all kinds of different beauty. I passionately hope to be able to be strong enough to reject it because it feels so unfair that I’m paid less than men, and yet I’m expected to spend more money on fighting time and gravity. It feels so unbelievably offensive to me that we can find men who are aged so dignified and sexy and looking wise, and we violently reject those same qualities in a woman’s face because we don’t want to think of women as dignified and wise and with knowledge and experience because that’s someone autonomous who doesn’t need other people as much. We love the little girl aesthetic who looks helpless and like “I need a man to come help me.”

Emma [00:51:44] Mhm.

Jameela [00:51:44] We love someone who does not look like they have that autonomy, and that to me is incredibly disturbing. And the older I get, I’m sure people will say, “Well that’s just because you’re not young anymore.” It’s really not that. I felt this way my whole life. It was the one area that didn’t manage to get me. You know, I took every fucking laxative and, you know, weight loss drug and laser, and God knows what I’ve done to my poor, poor, broken body. I have given in to beauty norms. I wear makeup or I participate in fashion trends. But this is the last bit of me that the patriarchy hasn’t yet touched. And I’m dying to be able to preserve it and to encourage it and others because I want my wisdom to show on my face. I don’t want to diminish my experience by erasing all trace of it as if it were something to be ashamed of. I’m incredibly proud of having lived. And so I hope that that resonates with someone out there that we, if we all stop conforming in uniform, we can start to kill the trend, especially women in my position who have so much power and all sides of our platform. Don’t airbrush the photographs. Don’t look 21 in your magazine when you’re 50. Reject the airbrushing. Reject that, if you can, reject that. And it’s so hard to ask this of these women because they do get less opportunities when they do certain things. I have never done a beauty campaign or not since I was like 22 before I took a stance on airbrushing because I refuse when I get approached by big brands to do makeup campaigns or hair campaigns. We can’t agree on the fact that I don’t want to be airbrushed.

Emma [00:53:15] Wow.

Jameela [00:53:16] We cannot agree on that, so I’ve cost myself millions and millions and millions of dollars. World’s smallest violin. But I’m just saying that I have

Emma [00:53:22] No I hear it.

Jameela [00:53:22] But I have been denied the opportunity to participate and be able to have financial independence, etc. in that way. Because I’m saying it’s bad not just for other girls who look at me or older women who are my age and then are going to see me not age at the same time as them in the same way. It’s fucking bad for me. It’s bad for my brain to see these images that I then feel like I have to live up to. I’ve said this before in this podcast that when we filter our faces, we then create an anxiety. We create a disparity between what we present to the world and what we look like in front of the mirror. That then makes us feel like shit. We do. We are participating now and doing this to ourselves. And one thing you brought up just now, as we do, we must remember our autonomy. We must remember

Emma [00:54:06] Mhm.

Jameela [00:54:06] That as much as these things are normalized and very difficult to resist, we have that autonomy fundamentally to at some point say “when is it going to be too much money or too painful or too time consuming or too anxiety giving for us to have to participate in this?” Sorry to rant.

Emma [00:54:22] Yeah.

Jameela [00:54:22] But this is why

Emma [00:54:23] No.

Jameela [00:54:23] I wanted you on the show because I think what you’ve written about was, just really spoke to me and I think everyone should read this book because it’s so hard to argue with.

Emma [00:54:30] Thank you. Thank you so much. I love what you were saying about it being for you and about I don’t know if you use the word neurosis, but I’m going to use the word neurosis for myself. That’s what, like if I start fixing something that for me, that’s the path to madness.

Jameela [00:54:46] Slippery slope.

Emma [00:54:46] Because I know I’ll never stop finding, quote unquote flaws. Yeah, I basically, I know for me that would be like very, it would lead to like mental. We started the conversation talking about mental health. My mental health would not be good if I started, you know, trying to fix perceived, perceived flaws. But one of the reasons that I wanted to disrupt the. Okay, so we’re told that, like if we have, if we possess this thing that’s called beauty, we will have access to love and security and, you know, care and protection and kindness. And I think one of the reasons we aspire to it because, is because we think it will provide us with those things. So I very specifically wanted to talk about women in the book, you know who are or have been perceived, or perceived as beautiful. And there’s like a consensus, you know, that these are beautiful women and it hasn’t translated into those things for them. And I’m like, given that that is what, what most people on the earth want, want to experience and strive for is, you know, kind of love, security and protection. Why don’t we create a world where, you know, those things are available to us? Why don’t we build a world where that is, that’s our goal, to make those things accessible to everybody rather than thinking beauty is like the path to those things, or beauty is like the price that you have to pay in order to secure those things. When we also know that even if you’re seen as being in possession of beauty, that does not necessarily translate into those things at all.

Jameela [00:56:32] No, it doesn’t. A lot of those people that I know are single and, and not happy or whatever. I think it’s always ultimately down to when it comes to sustained connection, down to who you as individuals are when in combination with each other. Right? It’s just like, it’s only, there’s only so much that a face or a body is going to be able to sustain in a long term relationship is not to say that the more you focus on your face and body, therefore you can’t have love. That’s not what I’m saying at all. But but I will say that really upsets me for the people who do go to extreme lengths to reach these ideals that maybe they weren’t necessarily born, you know, resembling is that our culture also ridicules those people. Men constantly, openly on podcasts, ridicule the duck lip or the Botox face or the actresses who are in their fifties who suddenly looked incredibly young. We make fun of their face lift, we’re always looking to see what did she do, what magic trick

Emma [00:57:29] Mm.

Jameela [00:57:30] Does she use, the way that people ridicule the Kardashians, and the way that they look and the way that like it just feels like open season on those women’s bodies, whether they’re big, whether they’re small, whether they look young, whether they look old, and yet still they are demolished over their looks cause now they weren’t born with those looks and now they might look plastic or any of those other things. We just openly mock the women who then go to these extremes that they are told to go to to meet these ideals. It’s fucking infuriating. It’s like a trap.

Emma [00:57:58] It’s a trap, and it’s a complete contradiction. And it’s like when you’re like, deep in it, it’s like no matter what you do, it’s the wrong thing. You will be, like, pilloried for. Like either you are too obsessed and invested in your appearance or the other end of the spectrum. You’ve let yourself go.

Jameela [00:58:16] Oh my god.

Emma [00:58:17] And you’re completely, like, demolished for that as well, you know? I found Pamela Anderson recently, like, so powerful, like her decision to not wear makeup, given particularly the type of beauty that she was defined for having, you know. So for her to be in her fifties and to be at Paris Fashion Week with no makeup.

Jameela [00:58:38] I love the Pamela Anderson thing, but I also do feel like there was a part of some of us who were watching that who also got, it also felt like that was, it was became such a big deal that, again, they managed to make it somehow reductive or then a slight on the women who are her age, who do wear makeup. Again, that got weaponized against other women and that became the new superior thing to do.

[00:59:01] See, this is the thing.

[00:59:01] Or hear rumblings of people then being like, Oh shit, so should I wear makeup to fashion week? It’s so frustrating that everything has to be a uniform. Everything has to be a trend. Everything has to control everything. Everyone has to be the same. The way we glamorize and glorify everything is always a way to say, “this is amazing and your shit, whatever you’re doing, that isn’t the new thing that we’ve decided we like is shit.” And by the way, when it comes to makeup trends, we go in and out of like natural soft girl makeup, which means they’re about to sell the shit out of skincare to you because you have to have this kind of, quote unquote flawless skin in order to be able to have the no makeup look.

Jameela [00:59:39] And then we go back-

Emma [00:59:40] Haha!

Jammela [00:59:40] To cake yourself with makeup, 15 layers, powder, contour, etc. And then that’s going to give you maybe bad skin. So now you’ve got to go and spend all the money on the skincare cause clean girl that is actually back in. And we’re not doing intensive colors and gems and beads like euphoria. We just get swung back and forth to be sold shit all the time.

Emma [01:00:00] But it’s the binary again though. It’s like, it’s always the binary. So I feel like what Pamela Anderson is doing is not like superior to what anybody else is doing. And it’s not like, now this is what we must do. It’s just broadening. We need to be more holistic.

Jameela [01:00:14] Oh totally.

Emma [01:00:14] It’s just broadening the range of options.

Jameela [01:00:16] Totally, totally.

Emma [01:00:16] And I want to see, I want it to be normalized to see more women who aren’t wearing makeup, but I don’t want it to be pilloried, to pillory women who are wearing makeup.

Jameela [01:00:24] Totally. It is a bit annoying that Tracee Ellis Ross has gone without makeup loads of times. Like maybe, just maybe, won’t like a lick of lipstick. And no one’s really acknowledged that because I think she’s just like also such an amazing role model. But what I was going to say is that I totally, I’m not in any way criticizing Pamela Anderson for this. I’m saying the media frenzy that came out felt as though it turned once again into a new thing of this is the new thing, bitches.

Emma [01:00:48] Yeah.

Jameela [01:00:48] So you better fall in line. My question to you before we go is a difficult one.

Emma [01:00:53] Great.

[01:00:53] But I think it’s an important one to ask, which is that, however much you intellectualize the history of the beauty standards and you understand the context and you understand how fucked patriarchy and capitalism is, however much I was going back and forth on those planes between England and Pakistan and recognizing that these beauty ideals can’t really mean anything because they’re completely different at the other end of a plane journey. How do people actually download this into their brains? Like, how do we actually in a world that is still very much so currently programed towards these singular ideals, this uniform? When people read your book or they hear us both talking where we’re both wearing a bit of makeup, you know what I mean, we’re both still participating in the-

Emma [01:01:39] Yeah for sure.

Jameela [01:01:39] The beauty ideal. Exactly.

Emma [01:01:39] Yeah, yeah for sure.

Jameela [01:01:43] How do we actually divorce ourselves from it? And realistically, how does someone who’s listening to this go, okay, I understand this is fact. I understand this is by design. I understand this is to control and destroy my life and make me spend my money.

Emma [01:01:55] Hahaha.

Jameela [01:01:55] But how do I actually break away from this?

Emma [01:01:58] Okay. So I want to, like, disentangle like the pain and all of the kind of like oppressiveness that exists within our beauty culture from the actual kind of like joy and like kind of pleasure of ritual and sensuality that also exists in it. And as you correctly pointed out, I’m wearing makeup.

Jameela [01:02:23] So am I.

Emma [01:02:24] I absolutely love makeup, but it was very much my intention not to pillory people who are wearing makeup. One of the pleasures, like in having a body, is if you so choose, being able to adorn it, being able to luxuriate in like the sensuality, like of having a body. I also think if you wish to, the idea of adorning yourself to make yourself look more attractive to, you know, experience desirability, these things are actually things that, you know, we should just be able to enjoy. It’s because of the way that they are so deeply entangled with the politics of like competition and with capitalism that they, the more oppressive aspects of them have come to the fore. But how can we kind of disentangle the pleasure from the pain is what the book is trying to do.

Jameela [01:03:22] And the book is also calling for us to find beauty in other parts of ourselves, in our brain and our ability for, to create or, you know, the things that we see in the world.

Emma [01:03:34] Thank you. Yeah. Also in the book, I’m really talking about beauty, not just being something that you are, but something that you do. And again, I take examples from different cultures where beauty was seen as existing in the relationships that exist between things, the relationships that exist between people. We live in a culture that has, you know, intentionally over millennia contributed to us experiencing like profound disconnection within ourselves and disconnection from each other and from the natural world. And it’s about, and when we are in that state of like deep disconnection, we are vulnerable and like, you know, kind of malleable to these predatory forces and trying to find it. When I talk about like different practices in the book, I talk about my relationship with like transcendental meditation, but different practices that can make us like less susceptible and vulnerable to these kind of like predatory forces and ways that beauty can be perceived as a verb, as something that we do, not just something that we are.

Jameela [01:04:37] Yeah, totally. And my personal advice to anyone would be things that helped me is saying “dog” into my phone all the time and only looking at dog videos so that my algorithm would change from make up videos and beauty and fashion stuff to more being funny videos of animals getting off my phone. I don’t, you know, buy a lot of fashion magazines unless there’s a really interesting interview with someone I love in it. I have started to kind of decolonize and deep patriarchy my brain to get away from these images. And I actively follow older women and curvy women and women who aren’t just curvy and the quote unquote, right way that you’re supposed to be curvy.

Emma [01:05:16] Yes.

Jameela [01:05:17] And it’s been insane to watch that since I’ve done that, since I started to diversify what I see, since I don’t look really in the mirror beyond first thing in the morning and last thing at night to like, you know, wash my face and clean it and put some moisturizer on and check there’s no like, actual shit on it. I don’t know how that would happen, but I-

Emma [01:05:34] Haha.

Jameela [01:05:36] I have personally made the decision to start and I’m aware that I exist within privilege and people will be able to dismiss me for that. But I am also a woman in Hollywood who’s turning 40 in a few years, who is being pressured in all of these ways. I’m being denied opportunities for these things, and still I’m choosing to resist, not because I’m some great martyr, but because I’m trying to protect the rest of my life. I’m thinking about my third act, and I don’t want it to be as sad-

Emma [01:05:57] Yeah.

Jameela [01:05:57] And anxious as I know it will be if I allow myself to try to keep up with who I was when I was 21 years old. And I also hated myself when I was 21 years old. It’s just a trap. So divorce yourself from things, from the propaganda that tells you to stay in the trap. Go in the trap. You’ll be safe there. You’ll be loved. You’ll get a nice lover. You’ll have more sex if you’re in the trap. Too distracted to have sex. I became really boring when I was consumed with my appearance. I actually wasn’t that interesting to go on a date with because I hadn’t done anything other than think about myself in the way that I look and how I can cheat time and gravity and thinness. So just really actively make a conscious effort to start to participate in things that you do, who you are, time with your friends, things that give you

Emma [01:06:43] Yes.

Jameela [01:06:43] A natural rush of dopamine in a way that starving himself never will, in a way that putting something really painful in your face probably won’t. Do whatever you want, do whatever you want to your face, but try to work on making sure it’s a choice by removing all of the conditioning around you, so that you actually have a fighting chance, a fighting chance of really making an autonomous choice cause how can it be an autonomous choice when we’re constantly bombarded with this imagery. Get away from it, work on yourself, start building towards your third act, and try to make it as unmiserable as possible.

Emma [01:07:15] I love that.

Jameela [01:07:16] I really appreciate you. I know you have to go because you are very busy and you’re a Mum. Will you tell me before you go? What do you weigh?

Emma [01:07:23] Oh, what do I weigh? So for me, like my relationship to nature, I left the city so that I could be close to the sea. And, like I swim in the cold English sea very regularly, which is never something that I, that I really saw in my future. And also, I’m really, like, focusing on like investing in and cultivating my friendships not just with women like, but friendships with men as well. I was definitely somebody that always saw romantic relationships as the primary site of my, of my intention and focus. And I think as part of all, a part of all of this, part of all of this, like thinking and writing I’ve been doing about like my appearance not being, you know, the kind of primary marker of my worth also has a relationship to where I put my attention in terms of my my friendships and relationships.

Jameela [01:08:25] That’s beautiful. Thank you for coming on today. Thank you for talking to me about all this. The book is so smart and so important. I really hope you have great success with it. And I’ll see you soon.

Emma [01:08:37] Much love.

Jameela [01:08:40] Thank you so much for listening to this week’s episode. I Weigh with Jameela Jamil is produced and researched by myself, Jameela Jamil, Erin Finnegan, Kimmie Gregory, and Amelia Chappelow. It is edited by Andrew Carson, and the beautiful music you are hearing now is made by my boyfriend, James Blake. And if you haven’t already, please rate, review, and subscribe to the show. It’s such a great way to show your support and helps me out massively. And lastly, at I Weight we would love to hear from you and share what you weigh at the end of this podcast. Please email us a voice recording, sharing what you weigh at iweighpodcast@gmail.com. And now we would love to pass the mic to one of our listeners.

Listener [01:09:17] I weight being talented. I weigh being intelligent and curious and trying to learn more and more about different things every day. I weigh a lot. I weigh a lot of good things. And another thing that I weigh is pride and confidence for the woman that I am and the woman that I am becoming.

Recent Episodes

See AllNovember 25, 2024

This week Jameela is bidding a fond farewell to the I Weigh Podcast and answering listener questions.

November 21, 2024

EP. 241.5 — Introducing The Optimist Project with Yara Shahidi

Guest Yara Shahidi Janelle Monáe

We’re sharing a new podcast with you on the I Weigh feed. Host Yara Shahidi sits down with incredible changemakers to unlock their secrets to conquering life, love, career, and everything in between with unwavering confidence and hope.

November 18, 2024

EP. 241 — Dismantling Gender Violence with Dr Jackson Katz

Guest Jackson Katz

Jameela welcomes the world-leading educator on gender violence, Dr Jackson Katz (Every Man, Tough Guise) back to her I Weigh podcast for a fresh discussion on why violence against women is a men’s issue, and what we all can do to make a difference.